Black History Month 2018 – Learn and Celebrate with Us!

Black History Month gives us the opportunity to look at an important and too often overlooked or undervalued part of American, New York, and neighborhood history and highlighting. Within our neighborhoods, there is an incredible array of African American histories, contributions, and culture all around us — sometimes hiding in plain sight.

African Americans have been a crucial part of the history of the Village and East Village since the early 1600s — the earliest period of non-native settlement in the area. In fact, in many parts of our neighborhoods, African Americans were the first non-native settlers.

This year we’re planning three special programs to outline key moments of the African American experience in our neighborhoods’ history:

- On Tuesday, February 6th, Enslaved and Free Africans in Lower Manhattan, 1613-1741, presented by award-winning historian Sylviane A. Diouf, will explore the early slave trade, Africans’ ownership of land during Dutch rule, slave revolts, and the Negros Burial Ground.

- On Tuesday, February 13th, Recovering the Lost Origins of the Black Arts Movement in Greenwich Village, Harlem and San Francisco with professor and writer Komozi Woodard will explore a generation of writers and artists who forged a new and enduring cultural vision that changed the world.

- On Wednesday, February 17th, The Genius of Little Africa: Black Radical Thinkers, Entrepreneurs, and Abolitionists in the Village with educator and curator Jamila Brathwaite will explore this former Village enclave of free and self-emancipated people living, working, and thriving within the confines of an oppressive society, featuring several little-known but not forgotten abolitionists, entrepreneurs, and radical thinkers whose efforts enhanced the lives of many.

Register for one or all on our website, or just by clicking on each.

While you’re waiting for these great programs to begin, hopefully this will whet your appetite for all this month has to offer.

Black History Month was created by historian Carter G. Woodson, starting off as Negro History Week in 1925. Woodson’s hope was to raise awareness of African Americans’ contributions to civilization; the week originally marked the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. The celebration was expanded to a month in 1976 and is observed around the world.

Greenwich Village once contained the largest African-American community in New York. It was home to sites like The Freedmen’s Bank, created to aid African-Americans in their transition from slavery to freedom in 1865; early African-American churches such as AME Zion Church, the first black church in New York and the founding church of the Zion AME denomination, Abyssinian Baptist Church, New York’s second black church, and St. Benefict the Moor Church, the first black Catholic church in the north, as well as and integrated, abolitionist churches such as the Spring Street Presbyterian Churhc; theaters such as William Brown’s African Grove Theatre, an African-American owned and operated theater that presented productions with an African-American cast; and schools such as The African Free School, the first school for African Americans in the country, founded on November 2, 1787 by the New-York Manumission Society and founding fathers Alexander Hamilton and John Jay.

Sadly, none of these structures survive; they can all be found on GVSHP’s Civil Rights and Social Justice Map, and many will be discussed at our upcoming programs.

Additionally, in this wonderful article by historian Christopher Moore, who called the Village the first African American community in North America, he writes:

The first known person of African descent to arrive on Manhattan Jan (Juan)Rodrigues, who was among the navigators, traders, pirates, and fishermen who traversed the Atlantic as free men, before and during the slavery era. Rodrigues, a free black sailor from Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) arrived in 1613, setting up a trading post with the native Lenape people on Manhattan Island.

The first enslaved African arrived in New Amsterdam in 1625, as laborers for the Dutch West India Company (WIC). The WIC, whose profits were chiefly from commerce reliant upon slave labor (and later the slave trade), was then pursuing its interest in the fur trade, which had been cultivated by early traders like Rodrigues. Along with European merchants, traders, sailors, and farms, these enslaved workers helped to establish the early colony. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Africans were an important part of the city’s population, reaching a peak of over 20 percent at the middle of the eighteenth century.

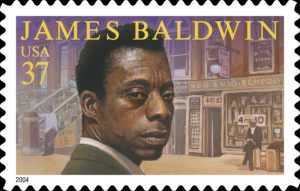

More recently, the Village boasted the first classes in African American History at The New School, taught by W.E.B. DuBois, the first home of the NAACP, the homes and work of Jean Michael Basquiat, Lorraine Hansberry (we unveiled a historic plaque at her home this past year), and James Baldwin, as well as the spot where Billie Holiday first sang “Strange Fruit,” Angela Davis’s imprisonment, and one of the key launching pads of the Black Arts Movement.

In his post about the Black Arts Movement last year, my colleague Harry highlighted 27 Cooper Square, where movement leaders Amiri Baraka and his then-wife Hettie Jones lived. He wrote:

Together, Hettie and LeRoi produced their magazine “Yugen” and Totem Press books there… Thanks to its proximity to the original Five Spot, writers and artists, including Allen Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara and others under the “Beat” and Black Mountain labels, were frequent visitors. Later in the 60’s, the house was the “headquarters” of the Black Arts Movement, an American literary movement to advance “social engagement” as a sine qua non of its aesthetic. Here is a good piece “Rethinking the Black Power Movement” by Komozi Woodard of Sarah Lawrence College that situates the Black Arts Movement in a larger context.

Harry’s connection with Komozi Woodard in his post is how we came to be welcoming Professor Woodard to speak about the Black Arts Movement on Tuesday, February 13th. Professor Woodard’s talk will go deeper and broader into its roots in the Village and its extensions up to Harlem and all the way to San Francisco, not to mention around the world.

Join us to go deeper into individual experiences, historical records, poetry readings, and much more at our Black History Month public programs this February. Event videos and photos will be available following the programs. Looking forward to learning together and celebrating Black history!