Elizabeth Jennings Graham — New York’s Rosa Parks, A Century Earlier

Exploring African American history in our neighborhoods, today we look at Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a woman who, in her simple quest to get to her church on East 6th Street sparked one of earliest challenges to institutionalized racial discrimination in public accommodations. In 1854 Graham challenged the segregation of New York City’s trasportation system, about 100 years before Rosa Parks’ historic refusal to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Elizabeth Jennings (Graham was her married name) was born in New York City in 1826 or 1830 (there are different accounts of her birth year) to Thomas and Elizabeth Jennings, prominent members of New York City’s black community. Thomas, a tailor by trade, was the first African American to hold a patent in the United States (for renovating garments) and one of the founders of New York’s Abyssinian Baptist Church. He and later his daughter were involved in many social and religious organizations.

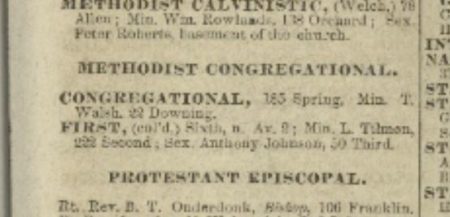

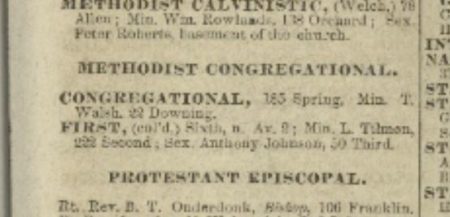

On July 16, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings boarded a streetcar of the Third Avenue Railway Company on her way to play the organ at the First Methodist Congregational Colored Church at 23-25 East 6th Street (today’s 228 East 6th Street, between Cooper Square and 2nd Avenue; the church has since been demolished and replaced with a tenement in 1890). At the time, public transportation typically did not serve African American passengers, but Jennings boarded the streetcar despite the reluctance of the conductor. However, soon after boarding, she was forcibly removed by the conductor and a policeman at the corner of Chatham Street (present-day Park Row) and Pearl Street.

Elizabeth wrote a letter about this experience which was published by Frederick Douglass and Horace Greeley in the New York Tribune. This led to a massive protest from New York’s African American community, and beyond. As published in the Tribune:

She got upon one of the Company’s cars last summer, on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered, but she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.

Jennings sued the company, the driver, and the conductor. She was represented by a young lawyer and future President of the United States, Chester A. Arthur. The court found in favor of Jennings and awarded her $225 in damages. As stated by the court, “Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence.” While the case did not prevent future instances of African Americans being denied the use of public transportation, it did impact and set precedent for transit discrimination trials in the future.

To learn about other important sites connected to African American civil rights history in our neighborhoods, please see Village Preservation’s Civil Rights and Social Justice map. To learn about more sites in the East Village connected to African American history, check out this tour on our East Village Building Blocks website.

One response to “Elizabeth Jennings Graham — New York’s Rosa Parks, A Century Earlier”