Dr. Simon Baruch and the Bathhouse Movement

The buildings we pass in our neighborhoods can offer windows into some rather specific aspects of New York history, and the interesting and sometimes complicated figures involved in the city’s development. One prominent example is what we can learn from some buildings in our neighborhood about public bathing habits and hygiene during the 19th century.

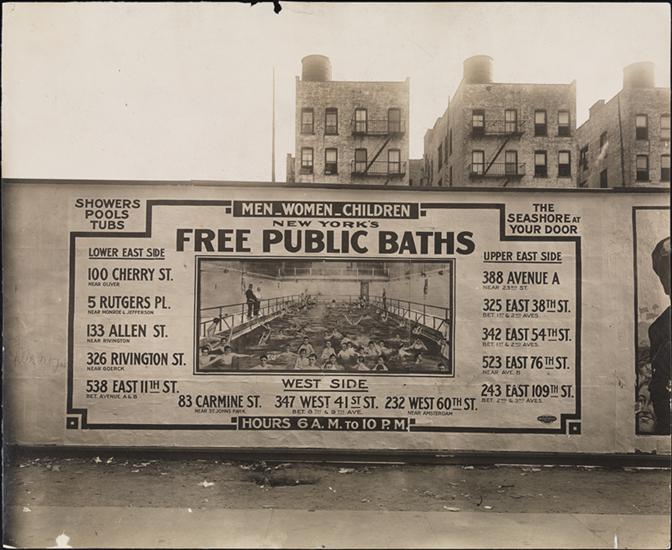

The City of New York opened fourteen public bathing facilities between 1901 and 1914. Allowing New York’s poor communities to wash and care for themselves, these free bathhouses came about with the help of Dr. Simon Baruch (July 29, 1840 – June 3, 1921), a physician who fiercely advocated for access to bathing and wellness facilities in the United State’s most populated cities.

Surgeon and Prisoner of War

Simon Baruch began his life in 1840 in Schwersenz, a small town in Poland, before emigrating to South Carolina as a teenager. He received his medical degree in 1862 from the Medical College of Virginia and served as a surgeon for the Confederate Army in the Civil War. The Union Army captured Baruch twice as a prisoner. He described that his first captivity “would have been the most delightful of my war experiences,” had it not been for an illness he acquired during his imprisonment.

Following the war’s end in 1865, Baruch continued to practice in the South for a time. Later that year, he made his way to New York to work as an attending physician at the Medical Polyclinic of the North-Eastern Dispensary in Hell’s Kitchen, commonly treating poor and working-class people. A year later he was back in South Carolina, where he remained for over a decade. But in 1881 he returned to New York, where he became known as an active public health advocate and medical writer, and made great strides in medicine.

The Principles and Practice of Hydrotherapy

While teaching in South Carolina and serving as chair of the Board of Health, Baruch started to expand his study as he recognized the amount of unproven medical advice his colleagues offered to their patients. Through these alternative studies he explored the benefits of hydrotherapy – therapeutic spas, bathing, and other methods of healing the body with clean water. Some common procedures from that time show up in our modern spas and physical therapy, like stretching out pains in the body while underwater and bathing to encourage healing. Baruch’s 1898 publication, The Principles and Practice of Hydrotherapy, even suggests the radical benefits of drinking plenty of water. Other methods, though, appear to range from misguided to horribly inhumane, particularly in treating patients with mental illness.

Hydrotherapy, central to so many ancient cultures, gained quite a following in Europe during the first half of the 19th century, with advocates from Germany, Britain, and Austrian Silesia publishing their findings. But Baruch is among those credited with introducing hydrotherapy (more specifically, balneology) to the United States.

Government Action

Today, Baruch’s legacy remains most visible with the public bathhouses he fought to establish. He persuaded the State Legislature to require cities with a population of over 50,000 to provide free bathhouse facilities and got the ball rolling with an order for a public bath in New York City. The first such facility opened in 1897 on Centre Market Place between Broome and Centre Streets. This one, however, charged five cents for its services so couldn’t truly count as “public”.

The Clarkson Street Bathhouse

Within our neighborhoods, we find a couple of public bathhouses credited to Baruch’s advocacy. The Clarkson Street Bathhouse, located at 83 Carmine Street (now addressed as 1 Clarkson Street), opened in 1908 with “showers and tubs on the first two floors, a gym on the third floor and an open air classroom for sickly children on the roof.” Serving the largely Italian population of the South Village (and located within Area II of the Historic District), the bathhouse was designed by Renwick, Aspinwall and Tucker and cost approximately $132,954 to build. Today, the building houses the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center, named for the “Mayor of Greenwich Village,” 12-time-elected chairperson and 52-year member of Community Board 2. Run by NYC Parks, the facility houses plenty of space for sports, indoor and outdoor swimming, public events, and more. So, although altered, this historic bathhouse still stands, for people to enjoy some healthful activity!

11th Street Public Baths

The other grand display of Baruch’s work in our neighborhoods can be found at 538 East 11th Street, the Free Public Baths of the City of New York. Containing 7 bathtubs and 94 showers, architect Arnold W. Brunner built the Beaux-Arts style facility between 1904 and 1905. (Read about this building in Francis Morrone’s “A History of the East Village & Its Architecture” on page 114.) As part of Baruch’s and others’ campaigns for public health, these bathhouses allowed the poor to bathe and care for themselves, when tenement living didn’t yet provide this. During the hot summer months, it turned out that people enjoyed the baths more as a means to keep cool than to wash themselves.

Eventually, as tenements modernized and plumbing became available, public baths lost their visitors and began to close. This one closed in 1958 and became a warehouse and garage until 1995, when time photographer Eddie Adams purchased the space and converted it into a high-end fashion and corporate photography studio. Though it doesn’t serve the community exactly as it did a century ago, its impressive façade and history of health can still delight us.

Simon Baruch’s work also contributed to the Asser Levy Public Baths at East 23rd Street, also run by NYC Parks and designed by Arnold W. Brunner; the Rivington Street Municipal Bath, the first bathhouse built with public funds in NYC which was later named the Baruch bathhouse; and the West 60th Street Bathhouse, now the Gertrude Ederle Recreation Center. Multiple schools and residential buildings also bear his name. Of his advocacy for free bathhouses and the health of our communities, he said, “I consider that I have done more to save life and prevent the spread of disease in my work for public baths than in all my work as a physician.”

Read about the 11th Street Public Baths on East Village Building Blocks.

Read Francis Morrone’s report here, or watch the video of his May 21st lecture here.

I visited the East 11th St.Baths on Women;s Day. It was an incredible experience being among a group of naked women I didn’t know.I was too shy to strike up a conversation. There was a steam room, a room with a cold running water pool, and a room of cots to lie down on as well as a place to sit and relax. I think it may have been $12 fir 3 hours. At that time, $12 a week wasn’t something I could afford, especially since I had a bathtub and shower in my apartment. I had gone to it just that one time because it was in danger of closing and was trying to attract more women customers.

. . . amazing reminder of what was once an integral aspect of our ‘culture’ — at least in NYC, anyhow. Something no one (including myself) ever even thinks of today. This always fleetingly crosses my mind whenever I pass by one of the few remaining relics of this custom.