Asian-American History in Greenwich Village and the East Village

The Asian-American and Pacific Islander community has a more than 150-year-long history in the United States, dating back to the first wave of Chinese and Japanese immigrants settling on the West Coast. And while nearby neighborhoods like Chinatown or the Lower East Side may have been much more prominent hubs for Asian-Americans, Greenwich Village and the East Village nevertheless can boast a long and impressive roster of individuals, organizations, institutions, and events located here that played an important role in the story of Asian-Americans in our city and country — especially (and unsurprisingly) in relation to civil rights and the arts. It is here that rights were won; discrimination was given a human face; innovations in painting, writing, and sculpture took place; and people gathered to confront the challenges and opportunities presented by the world around them. Here are just a few of those inspiring individuals, places, and associations:

Key Sites and Organizations

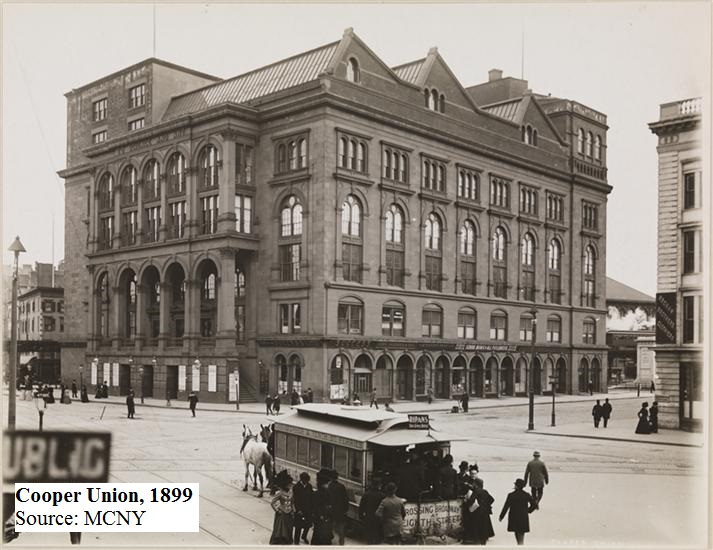

Chinese Equal Rights League founded and “Chinese American” coined, Cooper Union Great Hall

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art was founded in 1859 by American industrialist Peter Cooper, who dreamed of educating talented young people at an institution that was “open and free to all.” For over a century, the striking Italianate brownstone building has been an important site in New York City’s civil rights and social justice history. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and an individual New York City landmark in 1965.

On September 22, 1892, a group of 1,000 U.S. citizens and 200 Chinese merchants and laborers gathered at The Cooper Union’s Great Hall to protest the Geary Act, forming the Chinese Equal Rights League. The Geary Act, which had passed that year, required Chinese residents of the United States to carry a resident permit at all times. If a person did not carry a permit, they would risk deportation or a year’s worth of hard labor. Under the Geary Act, Chinese residents were also prohibited from bearing witness in court and from receiving bail in habeas corpus proceedings. At its first meeting, the Chinese Equal Rights League passed a resolution, published as a pamphlet, condemning both the Act’s immigration restrictions and its denial of citizenship to Chinese-Americans. The resolution demanded that the act make a formal distinction between recent Chinese immigrants and resident Chinese-Americans. The Philadelphia merchant Lee Sam Ping was elected president of the organization. Wong Chin Foo, a journalist and activist who is credited with founding the organization and with coining the term “Chinese-American,” was elected as secretary.

That same year, the Chinese-American community raised money to test the constitutionality of the Geary Act in Fong Yue-Ting v. the United States. Over the next decade, the Chinese Equal Rights League’s activism extended beyond its resistance to the Geary Act, focusing on the larger fight for civil rights for Chinese-Americans amidst the passage of increasingly strict immigration laws.

The Chinese Consulate and Chinese Mission, 26 West 9th Street

Around 1885, the Chinese Consulate, which was involved in activist efforts to protect the civil rights of Chinese-Americans, operated out of 26 West 9th Street. In 1902, the Consulate moved to another office on Lower Broadway, and Huie Kin, a prominent Chinese-American missionary, moved his family and his Chinese Mission from 14 University Place into this building, which also housed the headquarters of the Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association. The family turned the third and fourth floors into lodging for Chinese students who were unable to find rooms elsewhere due to discriminatory renting practices throughout the city. The building housing the Chinese Consulate was demolished and in 1923 replaced with the apartment building now located on the site.

The Chinese Guild, 23 St. Mark’s Place

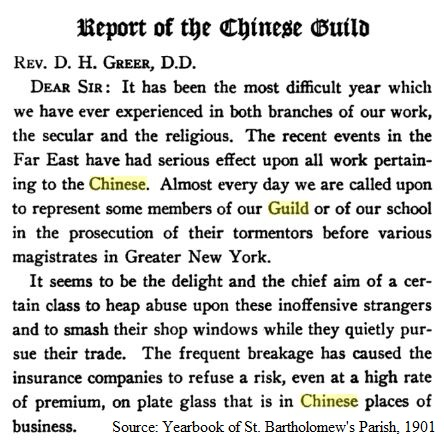

The Chinese Guild was founded in 1889 at 23 St. Mark’s Place. Though it was formed in partnership with St. Bartholomew’s Church at Madison Avenue and 44th Street, the Guild served primarily as a secular social welfare and legal advocacy organization for the city’s Chinese-American community. Membership cost $2 to join and $1 for every additional year. Guy Maine, formerly a Chinese tea merchant, acted as the superintendent. The Guild included up to 600 members, many of whom worked as laundrymen and faced frequent personal and institutional discrimination in their daily lives.

In addition to organizing a choir and Sunday school lessons for its members, The Guild provided English lessons, assistance with rental negotiations and legal documentation, and support contacting doctors, lawyers, and police. In 1891, Guy Maine was involved in 217 court cases regarding crimes committed against the Guild’s members, most of which involved assaults-and-batteries and broken laundry windows. “The Master Laundrymen’s Association,” a group of white steam-laundry owners threatened by the competition of Chinese laundries, would launch frequent attacks on businesses owned by Chinese-Americans, vandalizing their storefronts. As a result, insurance companies would not cover damage to plate glass used in Chinese-American-owned businesses. In a 1901 report, Superintendent Maine requested that the Guild be made a corporation, giving it the legal right to protect its members.

At this time, the building at 23 St. Mark’s Place included a library, music room, dining room, smoking room, gymnasium, and several bedrooms. It was open all day from 9 am until 10 pm. By 1898, The Chinese Guild had moved to the 9th floor of the new St. Bartholomew’s Parish House on East 42nd Street. 23 St. Mark’s Place survives today, albeit in highly altered form.

The International Workers Order, 80 Fifth Avenue

The International Workers Order (IWO) was located at 80 Fifth Avenue for its entire lifetime, from 1930 until 1954. This progressive mutual-benefit fraternal organization was a pioneering force in the U.S. labor movement, and took some incredibly powerful positions for civil rights and social justice — including against the brutal internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Congressman Vito Marcantonio, who served as the IWO’s vice president, supported the IWO’s many civil rights campaigns and was a strong opponent of the internment of Japanese-Americans. The Congressman received a number of letters of thanks for his efforts, including one from George Yoshioka, a War Relocation Camp Internee who wrote to Marcantonio from a camp in Amache, Colorado. Additionally, Marcantonio proposed a bill to remove the ban on Asian naturalization, receiving an acknowledgment of gratitude from the Japanese American Committee for Democracy. Grassroots members of the IWO also organized against the internment, and vehemently defended Japanese-Americans who were members of the Order.

From its beginning, the IWO was the frequent target of House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigations, and in 1954 the organization was disbanded following legal action undertaken by the state of New York. Nevertheless, the legacy of the IWO lives on in countless ways, as it laid the foundation for the continuing fight to provide and protect human rights for all Americans.

Village Preservation is leading the effort to seek landmark and zoning protections in the neighborhood south of Union Square, including this building. This historic neighborhood faces demolitions and out-of-scale new development stemming in large part from the tech industry:

Jade Mountain Chinese Restaurant, 197 Second Avenue

The Chinese restaurant Jade Mountain opened in 1931 and operated until 2007 following the death of its long-time owner, Reginald “Reggie” Chan, the year before. At the time of its operation, this was one of the few inexpensive Chinese food options in the East Village. The restaurant sported its signature vintage neon sign with the words “Chow Mein,” which has since been removed. In 1941, Jade Mountain hosted a lunch for refugees of the Spanish Civil War, at which Pete Seeger had his first performance. Seeger would go on to become an influential singer, songwriter, and civil rights and anti-war activist.

Prominent Chinese-Americans

Mabel Ping Hua Lee, Fifth Avenue

The first women’s suffrage parade in New York City took place along Fifth Avenue on May 4, 1912. One of the 10,000 marchers at the helm of the parade was Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (b. October 7, 1897). At 16 years old, Lee joined other Chinese-American women riding on horseback along the march route, from Washington Square Park to 27th Street. Both The New York Tribune and The New York Times wrote articles about her activism prior to and during this landmark event.

In 1912, Lee enrolled at Barnard College, where she joined the Chinese Students’ Association and wrote feminist essays for “The Chinese Students’ Monthly.” In 1915, she gave a speech at the Women’s Political Union’s Suffrage Shop, in which she encouraged the Chinese-American community to uplift the education and civic participation of women. Following her graduation from Barnard, Lee became the first Chinese-American woman to receive a Ph.D. in economics, from Columbia University. She published her research in the book “The Economic History of China.” When her father passed away in 1924, Lee assumed his role as the director of the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City.

Lee was also the founder of the Chinese Christian Center, a community center providing a health clinic, kindergarten, vocational training, and English classes. Though New York women gained the right to vote in 1917, and the 19th Amendment ending all gender-based voting discrimination was ratified in 1920, Chinese-American immigrant women and men could not vote until 1943. The Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited Chinese-American immigrants from obtaining United States citizenship and therefore voting rights. It remains undetermined whether Lee ever became a U.S. citizen and voted here.

Click here to see more historic images and newspaper clippings of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee.

Yun Gee, 51 East 10th Street

Artist, poet, philanthropist, teacher, writer, and inventor Yun Gee (February 22, 1906 — June 5, 1963) was the first Chinese-American artist to hold an important position in the history of Western contemporary art. Considered one of the great modernist avant-garde painters, Gee enjoys a number of other “firsts”: he was the first Chinese-born artist invited to join the Société des Artistes Indépendants; the first Chinese artist to display his work internationally; the first Chinese artist to show at MoMa; and the first Chinese artist to show in the salons of Paris. His art made frequent reference to his Chinese heritage either through form, style, or subject matter. He also developed his own signature style, Diamondism, which was derived from Cubism, and he promoted it through his art, writings, and teachings. From 1942 until his death in 1963, Gee lived and worked at 51 East 10th Street. Also in 1942, he married Helen Wimmer, who opened the country’s first commercial gallery focused on photography: Limelight photography gallery at 91 Seventh Avenue South (learn more in the “Transformative Women” tour of the Greenwich Village Historic District: Then & Now Photos and Tours map).

While living at 51 East 10th Street, Gee taught classes, and wrote about his theory of Diamondism. In 1943, Gee staged an exhibition at the Milch Galleries on West 57th Street to raise funds for the Music Box Canteen. Located at 68 Fifth Avenue, the Music Box Canteen was a celebrated World War II entertainment venue for GIs described at the time as “one of the most famous metropolitan service centers, and…‘a home away from home’ to thousands of servicemen.” This was not Gee’s first exhibit to benefit the allied forces; he had held others, the proceeds of which went to the British and American Ambulance Corps. The following year, in 1944, Gee’s work was showcased in the group exhibition “Portrait of America.” His work completed during his time at 51 East 10th Street includes Wanamaker Fire (1956), Old Broadway in Winter (1943-44), and Nude in Studio (1952).

Gee was also an inventor who designed a four-dimensional chess game. He received a patent in 1950 for a tongue and lip holding device “for aiding correct English speech.” There was even a report by a few periodicals from the time of his plans started in 1946 for a project of a tunnel to the moon which apparently he started in his own backyard in 1949. The projected cost was $9,000,000, and as reported in 1949, he had not gotten any financial backers to that date. Gee passed away in 1963.

Village Preservation is leading the effort to seek landmark and zoning protections in the neighborhood south of Union Square, including this building. This historic neighborhood faces demolitions and out-of-scale new development stemming in large part from the tech industry:

Martin Wong, 157 Avenue B

Martin Wong (July 11, 1946 — August 12, 1999) was an openly gay Chinese-American artist who played a key role in New York City’s downtown art scene of the 1980s and early 1990s. Wong was born on the west coast, and started his art career exhibiting in San Francisco in 1959. According to the Martin Wong Foundation, “his earliest works reflect[ed] the psychedelic era and his interest in the diverse cultures of Asia,” and included paintings, ceramics, and calligraphy that referenced Eastern mythologies and artistic traditions, local scenes of San Francisco, and toys. While in San Francisco, Wong completed outdoor exhibitions with the San Francisco Arts Festival, and created stage sets and props for a local alternative theater troupe, The Angles of Light.

Wong moved to the Lower East Side in 1978, living at the Meyers Hotel on Stanton Street and at 141 Ridge Street. During his time in lower Manhattan, Wong was involved in the downtown urban art scene and the local Chinese-American community. He befriended and collaborated with other artists such as Kiki Smith, David Wojnarowicz, and Keith Haring, among others. According to NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, the “most important friendship” to Wong was with Miguel Piñero, writer and co-founder of the Nuyorican Poets Café. Through Piñero, Wong developed strong ties with the local Puerto Rican-American community of the Loisaida (“Lower East Side”). At one point, Wong and Piñero were lovers and lived together at Wong’s Ridge Street apartment.

Wong’s artworks produced during his time in New York City included depictions of daily street life, sociopolitical issues like gentrification and displacement of low-income residents, the plight of Chinese-Americans from the Chinatowns of Manhattan and San Francisco, and cultural references to ancient Chinese art. He also produced homoerotic paintings and amassed a huge collection of graffiti art and graffiti-related publications, at the time when graffiti art wasn’t well regarded in the art world. According to his NYT obituary, Wong showcased at the Blinderman’s Semaphore Gallery spaces in SoHo (462 West Broadway) and the East Village (157 Avenue B) in 1984, 1985 and 1986. His final show was at the P.P.O.W. Gallery in SoHo in 1998.

His work could also be seen in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, MoMA, and the New-York Historical Society, and has been featured in numerous global exhibitions. Wong moved back to San Francisco in 1994 and continued to make art for 5 years. He passed away due to AIDS-related complications in 1999.

I.M. Pei, 100 and 110 Bleecker Street and 505 LaGuardia Place

I.M. Pei (April 26, 1917 — May 16, 2019) was a world renowned Chinese-American architect whose acclaimed designs include the Louvre Pyramid of Paris, the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing in Washington D.C., as well as a number of New York City structures such as the Four Seasons Hotel New York, and the Sundrome of JFK airport.

In 1964-1967, I.M. Pei & Associates designed University Village/Silver Towers, located between West Houston and Bleecker Streets. The design represents an important moment in the evolution of Pei’s career and in the evolution of modern design in general, as well as an important moment in Greenwich Village and New York’s architectural development. These buildings, their overall arrangement within this superblock, and their placement within the surrounding landscaping and larger street grid, are an unusually sensitive and sophisticated manifestation of 1960s modern design, and are some of New York’s most successful examples of cast-in-place concrete architecture, and perhaps its most successful residential design from this era.

The design won the American Institute of Architects National Honor Award and the City Club of New York’s Albert S. Bard Award in 1967, and Pei won the Pritzker Prize for Architecture in 1983 for his body of work up to that point in time. In 1966, Fortune Magazine dubbed Silver Towers one of “Ten Buildings That Climax an Era.” In typical Pei fashion, the design not only conveys the desire for structural truth and transparency typical of traditional modernism; it also displays a stylish, carefully articulated abstraction; acknowledges and subtly relates to the larger urban fabric around it; and gently shapes the experience of the pedestrian at street level. University Village/Silver Towers exhibits the synthesis of structural expressionism, the recognition of context and user which Pei would exemplify in his later designs, and which would inform the work of other pre-eminent late 20th century and 2lst century architects such as Richard Meier and Peter Eisenmann.

Following the plan of I.M. Pei, the complex includes an enlargement of a 1954 cubistic work by Pablo Picasso. The piece was completed by Picasso’s collaborator, the Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjar, in 1968. The shape of the sculpture plays off the “pinwheel” layout of the three Silver Towers buildings.

Village Preservation proposed and successfully fought to have University Village/Silver Towers designated as an individual NYC landmark in 2008.

Prominent Japanese-Americans

Jerry Fujikawa and Cynthia Gates Fujikawa, 150 First Avenue

Jerry Fujikawa was a Japanese-American actor who had a long career in films, television, and Broadway. Jerry debuted on Broadway in the five-time Tony Award winning play The Teahouse of the August Moon. He was very a familiar face to film and television audiences whose career spanned over 30 years, including a wide variety of movies, plays, and television shows; Mr. T and Tina, M*A*S*H, and Chinatown were but a few of his most recognizable roles.

Jerry was also one of over 110,000 Japanese-Americans interned in camps here in the United States during the course of World War II in response to American hysteria following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Jerry and his young family, along with his parents, his siblings, and their neighbors lost their constitutional rights and were forced to relocate to the Manzanar Camp in California in 1943. Most remained there until 1945.

Cynthia (Cyndy) Gates Fujikawa, Jerry’s daughter by a second marriage, followed in her father’s footsteps by becoming an actress herself. Cyndy’s pursuit of a career in the theater led her from California to New York in the 1990’s. Very shortly after her arrival, Cyndy began developing a one-woman play based upon her father’s life, his incarceration at Manzanar, and her quest to uncover the story of his mysterious first family and the search for a long-lost sister she never knew she had. Her submissions process brought her to Mabou Mines, an artist-driven, experimental East Village theater collective generating original works and re-imagined adaptations of classics.

Work at Mabou Mines is created through multi-disciplinary, technologically innovative collaborations among its members and a wide world of contemporary filmmakers, composers, writers, musicians, choreographers, puppeteers, and visual artists. Mabou Mines fosters the next generation of artists through mentorship and residencies, and remains a leading light in nurturing a variety of artistic voices at its artistic home at PS122, at 150 First Avenue. Cyndy found herself embraced by the company and was given the space and mentorship to create her work through an extended development process with the Mabou Mines Resident Artists Program. The result of Cyndy’s quest is a beautiful and searing autobiographical account, called Old Man River, which uncovers a father very different from the one she thought she knew: a man whose life was destroyed by his internment.

Miné Okubo Residence, 17 East 9th Street

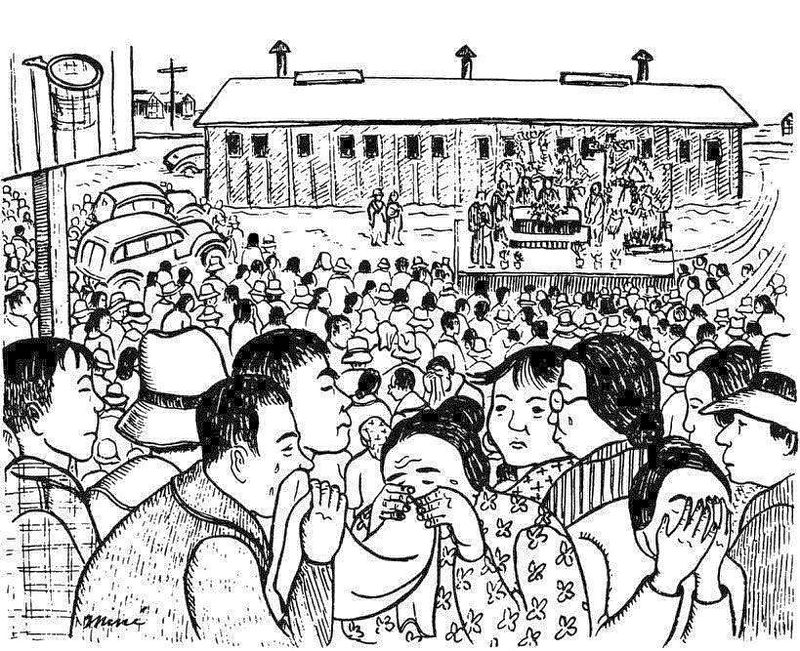

Miné Okubo was a Japanese-American artist born in Riverside, California, in 1912. She is best known for her 1946 book Citizen 13660, in which she recounts her experience in a Japanese-American internment camp, which was one of the first widely-circulated personal accounts of the repression and indignities faced by over 100,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II, and is considered to this day one of the most affecting pieces about that chapter in American history.

Okubo received her Master’s of Fine Arts from UC Berkeley in 1938 and spent two years traveling in France and Italy developing her skills as an artist. The outbreak of war in Europe forced her to return to the United States, at which point she began working for the Works Progress Administration’s art programs in San Francisco. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 called for the imprisonment of thousands of Japanese and Japanese-Americans living on the west coast. Okubo and her brother, Toku, were relocated to the internment camp Tanforan, which had been created as a “temporary assembly center” on a horse racing track in San Bruno, California. They were later relocated to the Topaz Camp in Utah, where they lived in harsh conditions with about nine thousand other Japanese-Americans. Okubo documented her experience at the camp in her sketchbook, recording images of the humiliation and everyday struggle of internment.

In time, Fortune magazine learned of her talent and offered her assignments. When the War Relocation Authority began allowing people to leave the camps and relocate to areas away from the Pacific Coast, Mine took the opportunity to move to New York City, where Fortune was located. Upon her arrival, she moved to 17 East 9th Street. It was here that she completed her work on Citizen 13660, named for the number assigned to her family unit, which contains more than two hundred pen and ink sketches. Though she eventually moved into another apartment, she lived in New York for the rest of her life, until 2001 when she died at age 88. Citizen 13660 is considered a classic of American literature and a forerunner of the graphic novel and memoir.

Isamu Noguchi Studio and Residence, 33 MacDougal Alley

Isamu Noguchi, the son of an Irish-American mother and Japanese father, was one of the 20th century’s most important and critically acclaimed artists with works spanning sculpture, dance, lighting, furniture, and landscapes. He was also an outspoken advocate against the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and though he could have avoided internment himself, was voluntarily interned in a camp for seven months. From 1942 until the late 1940s, Noguchi lived and worked at 33 MacDougal Alley, which was soon after demolished to make way for the high-rise apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue. Many of the residences on MacDougal Alley were former stables, built beginning in 1833 and converted to artist studios in the early 20th century.

By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Noguchi was already a well-known and accomplished sculptor. When anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States escalated following the attack, Noguchi formed “Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy” to speak out against the internment of Japanese-Americans, testifying at congressional hearings and lobbying government officials. Despite his and others’ efforts, over one hundred thousand Japanese-Americans were sent to internment camps, though this only applied to those living on the West Coast. Noguchi reached out to John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs, who persuaded him to travel to the Poston Internment Camp located on an Indian Reservation in Arizona to promote art in the community. He arrived in May 1942, becoming its only voluntary internee. He found the conditions unbearable, including the extreme desert heat. Although he worked on many projects to increase the quality of life for internees at Poston, he found the authorities had no intention of implementing them. He was viewed with suspicion by both internees, who thought him a spy and an outsider, and the authorities, to whom he was a troublesome interloper. Intelligence officers labeled him as a “suspicious person” due to his involvement in activism against internment. After he left the camp, Noguchi received a deportation order. The FBI accused him of espionage and launched a full investigation of Noguchi which ended only through the intervention of the ACLU. Noguchi would later retell his experience in the documentary series “The World at War.”

Click here to see photos of Isamu Noguchi in his 33 MacDougal Alley studio.

We hope this tour shines a spotlight on the AAPI community. Asian-Americans’ more than 150-year-history and experiences frequently involve great struggle, discrimination, determination, and achievement. The recent surge in anti-Asian-American/Pacific Islander hate crimes is only the latest reminder of this difficult and unresolved history; it reflects in many ways the discrimination faced by earlier generations, and the battles they fought, described above.

Village Preservation has long made a priority of elevating, preserving, and celebrating the histories and contributions of underrepresented groups in our neighborhoods including African Americans, LGBTQ people, women, immigrants, the Latinx community, and Asian-Americans.